Science writing update, June 2023 edition

Breastfeeding vs. infant formula; ultra-processed foods vs. 30 plants a week; AI vs. the human race; being lonely vs. smoking cigarettes. It's all here, plus a bunch of other interesting science links

Hello! You are, as ever, very welcome to this digest of my science writing from the past month. Below is a selection of articles on topics from baby feeding to diet to AI to loneliness to cash-transfers. You can see everything I’ve written at this link.

And I’ve also collected a bunch of other interesting science-related links for your delectation (skip right to those links by clicking here).

Oh, and: there might be some exciting news coming soon for those of you who enjoy listening to me talking about science. Watch this space.

Let’s get to it. Don’t forget to sign up if you’d like more of these monthly update-digest-roundup-newsletters:

Milky milky warm and tasty

I don’t think you have to be a hardcore libertarian to think that the UK’s laws on baby formula are crazy. You can’t advertise it, you can’t allow “buy one get one free” offers on it, and you can’t even put a picture of a baby on the front of the box, among many other restrictions on its sale and composition.

It’s as if baby formula was a dangerous substance - and many people seem to think it is - they argue that allowing it to be sold like any other food item might cause mothers to stop breastfeeding their babies, which could cause great harm. I wrote an article arguing that there’s no convincing scientific support for the idea that these laws work to “protect” breastfeeding, nor for the idea that they’re particularly proportionate:

…it’s not at all clear that the downside of allowing marketing for baby formula outweighs the downside of making life harder for non-breastfeeding mothers.

My tweets on this topic managed to kick off a great deal of Twitter discourse, much of which was extremely stupid, so here are the links if you like that sort of thing.

And just as a bonus, I also did a little Twitter thread on a new observational study that says breastfeeding is linked to better school exam results 16 years later (reported in much of the media, of course, as if it was a causal relationship). This also seems to have upset a few people.

You can call me AI

I’ve found that when I bring up the topic of the existential threat of AI, a lot of people look at me as if I’ve gone completely mental. That’s why I wrote this long article setting out, as clearly as possible, what people mean when they say that a rogue AI could be a severe danger to humanity.

Regardless of how plausible you think such a scenario is—and I also wrote a follow-up piece with even more possibilities—I hope this will be useful to send to your friends who might not have followed this debate, which has been happening on (let’s face it) pretty obscure internet forums for decades, particularly closely.

On the positive, non-doom, non-killer-robot side of the AI discourse, we also recently saw headlines about a new antibiotic “discovered using AI”. This article tries to put that claim in the proper context.

Food fads

I started to notice a new nutritional claim going around: that science tells us we should eat “30 different plants a week” for optimal gut health. Like me, your first reaction to hearing this might be “come on, man!”. But I decided to trace it back to its scientific source. And it turns out, perhaps predictably, that it’s bullshit.

The true nutritional buzzword/bogyeman du jour, though, is “Ultra-Processed Foods”. What does that term even mean? Is there something special about a “UPF”—some ingredient or ingredients—that makes it particularly unhealthy, or do these foods just taste really nice and that’s why people eat more of them? What does the evidence actually look like, here? I talked about those questions and more in my article on UPFs.

In any case, I’m feeling far more optimistic about the obesity epidemic: the cavalry really is on the way, in the form of GLP-1 agonists like semaglutide (marketed as Ozempic, Wegovy, and Rybelsus; but also even newer ones like tirzepatide). The UK’s NHS has just announced that you’ll soon be able to get semaglutide from your GP. This is extremely good news, as I discussed in this piece.

It’s lovely to see that the NHS has ignored all the daft anti-semaglutide arguments buzzing around in certain quarters: I’ve noticed that the Guardian seems to publish a surprisingly large number of articles of this nature so I started collecting them in this Twitter thread. The most recent one at the time of writing is perhaps the worst.

(The most annoying thing, though, is that with all this semaglutide discussion, I’ve had the jingle to the US Ozempic ad stuck in my head for days. “Oh, oh, oh, Ozempic!” to the tune of that old “It’s Magic” song by the (Scottish!) band Pilot. It’s a genius bit of marketing, but it is driving me slowly round the bend. And now it’ll do the same to you.)

Extend your Nature-al life

I’m always excited to see more research on cash transfers for people in developing countries: these seem like a really great way to improve people’s lives. So I was excited to read a new Nature paper that claimed to show, with data from dozens of countries, that these cash transfers help prevent people dying young.

But the analysis in the study makes some really basic missteps that undermine the whole argument. I wrote about the whole thing here (£):

But do [cash transfers] protect against early mortality? The sad thing is that, even after reading an article in Nature—the world’s “top” scientific journal, where you’d expect strong, definitive results—I don’t know.

Some dodgy comparisons

Loneliness: as bad for your health as smoking 20 a day? Well, not really: we know an awful lot more about the causal effects of smoking.

Flying in a private jet: as bad for the environment as owning three dogs? Well, not really: it heavily depends on how you do the analysis.

Maybe these kinds of comparisons aren’t actually very helpful, except as pure rhetoric.

And finally… mea culpa

Embarrassingly, the other week I shared what turned out to be a very bad preprint on fake “paper mill” research. This was a disturbing lesson in confirmation bias on my part: I knew the paper had shoddy methods, and even said so at the time, but I still tweeted and wrote about it anyway because it seemed to point in the same direction as other investigations of paper mills that I already knew about. Anyway, I deleted the tweet and wrote an extra critique of the study plus a column (£) about mistakes in science, including my own. A fuckup to be sure, and a good reminder to be extra-critical in future.

Things I didn’t write but that you might like anyway

And now for your monthly bonus links list:

There was a really nice one-off programme from BBC Radio 4 called “The Truth Police”, about data sleuths and why we need them. I pop up about halfway through, and you’ll also hear from Elisabeth Bik, Nick Brown, James Heathers, and Dorothy Bishop - all names you’ll likely know if you’ve been following the whole “replication crisis” story.

The first thing you need to know is that I’m not sharing what I’m about to share because a book that covered this topic beat my book to an award a couple of years ago. That’s not what this is about, honest! I’m glad we’ve established that. Now: there’s been a huge thing in books, articles, podcasts, and scientific papers in recent years about the “wood wide web” - the claim that trees can share resources, and maybe even communicate(!), because there are networks of fungi linking them up underground. Well, maybe the whole thing turns out to be based on exaggeration of the scant evidence. “Among peer reviewed papers published in 2022, fewer than half the statements made about the original field studies could be considered accurate”. Oops!

Is it possible for a scientist to publish a study every two days? Turns out technically the answer is “yes”. But you might wonder whether (a) the studies are any good and (b) whether the scientist in question actually contributed anything beyond signing his name.

And as if the scientific literature didn’t include enough low-quality research papers, now high-school kids are getting in on the game (often with help from pushy parents who can pay for their paper to be published).

Of the two most famous psychology studies of the 1960s/70s*, Milgram’s gets a better rap than Zimbardo’s. Mainly that’s because, unlike the Zimbardo’s Stanford Prison “Experiment” (which wasn’t actually an experiment and was a weird semi-theatrical occurrence where Zimbardo himself played a heavy role), Milgram’s studies actually had data and occurred across many hundreds of participants. But in this thread, Shane Littrell points to several sources that remind us that Milgram’s research was extremely shoddy as well, not to mention very difficult to interpret.

How many psychology studies are direct replications of previous work? According to this analysis by Beth Clarke shared at the recent Metascience conference, not very many: about 1 in 500 (though it has increased recently, thank heavens). I wonder whether this number would be higher or lower in other, non-psychology research fields.

What on Earth is happening in the very weird world of “hydroxychloroquine for COVID” research?

I loved this: a useful taxonomy of all the “persuasive communication devices” (read: sleazy writing tricks) that scientists use in studies to mischaracterise and oversell their results.

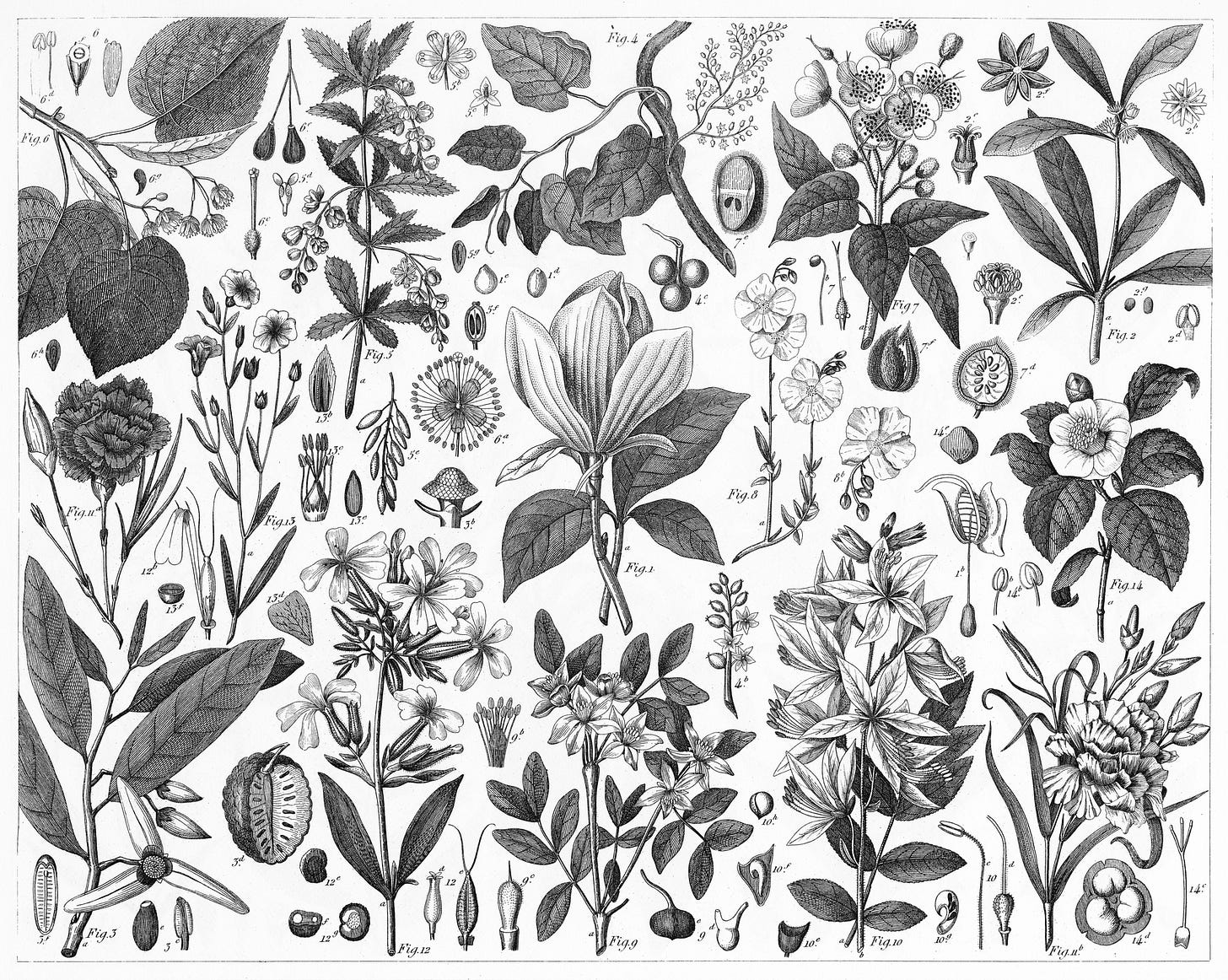

Image credit: Getty

Unimportant P.S.: This shouldn’t make any difference to anything because the old URL still works too, but due to the recent nonsense where Twitter was (is?) throttling links to Substack, you might have noticed that I’ve changed the main URL for this site, merging it with the site I made for my book when it came out: www.sciencefictions.org.

*Edit 10 June 2023: Milgram’s experiments took place in the 1960s, not 1970s. They came to popular attention in the mid-70s when Milgram published his book, but had all happened a decade earlier. Now corrected above.

fyi Milgram's studies were early 60s. People often note they were conducted before the rebellious counter-culture, anti-war movement in the U.S..

I'm really curious to learn more about Ozempic long-term effects in the coming months and years. I have a few friends (here in the US) who were prescribed it, but then insurance said they'd stop covering it so they're gonna go off soon. Will be interesting to see if they quickly regain the weight...

Have also heard some rumblings about unexpected off-target effects on a variety of addictions/cravings and compulsions in Ozempic users, with some anecdotal reports of people finding it easier to quit smoking. Is there any high-quality research evaluating these early claims?